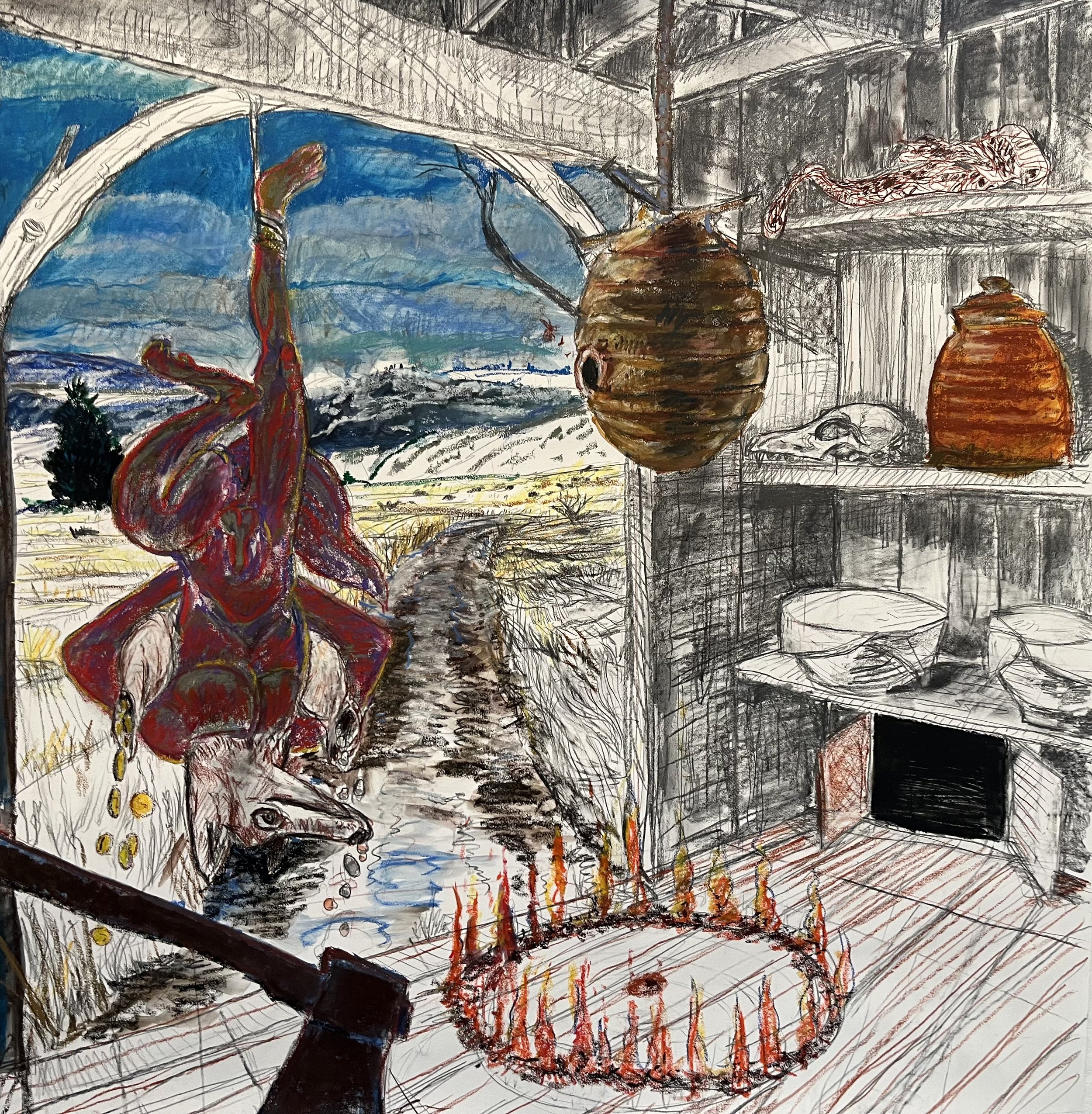

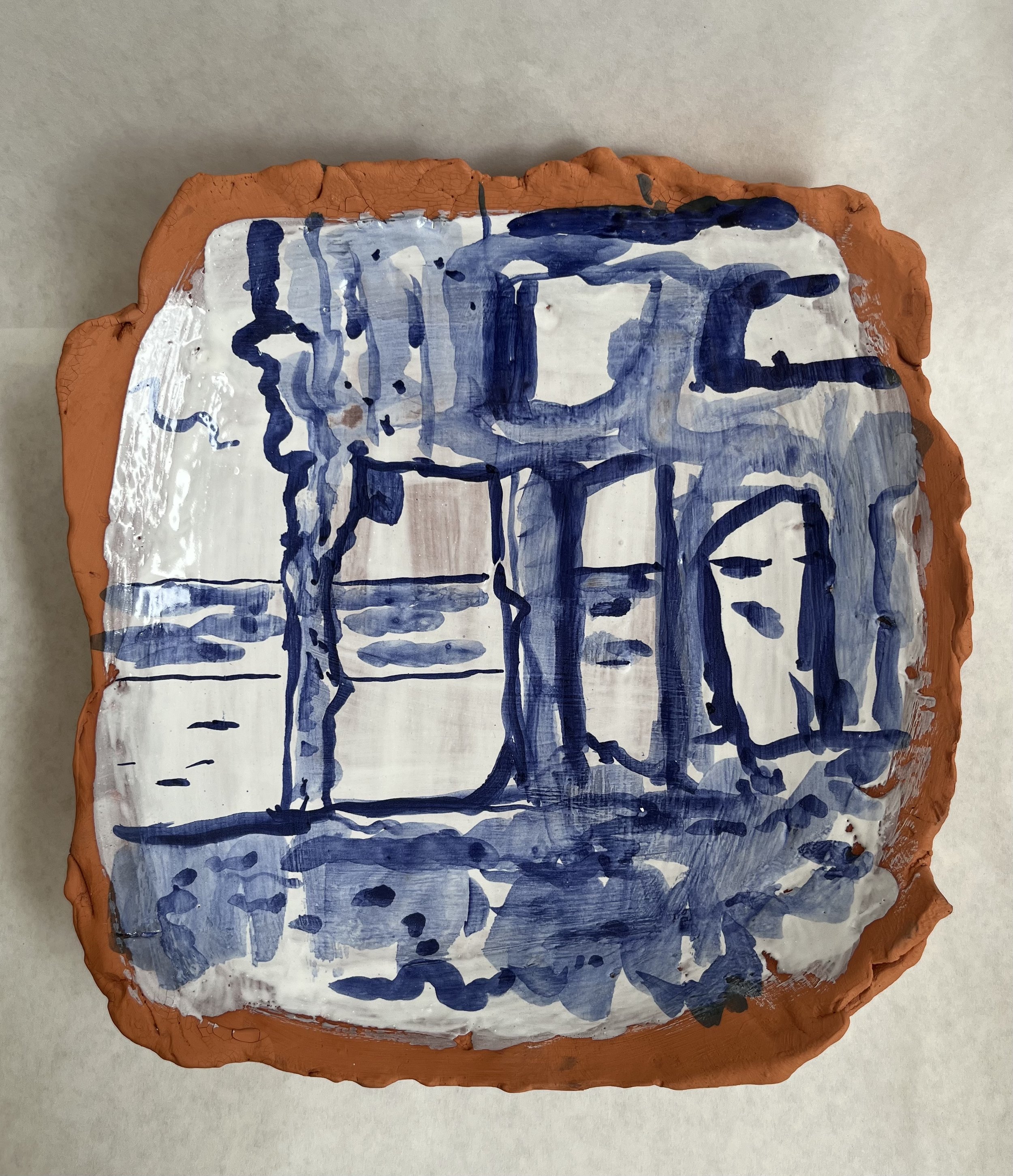

WHEN I MOVED TO PORTLAND from New Mexico in the late 1990s, I was creating sculptural clay vessels and drawings. The vessels referenced Northwest Coast feast bowls and burial canoes, earth architecture, and geology. The surfaces looked ripped, charred, and occasionally fleshy. In New Mexico, the integration of indigenous Hispanic and European histories, not to mention the geology—striped and splendid for all to see—really changed me. I worked for a while with Jicarilla Apache potter Felipe Ortega in La Madera, digging clay and living in his adobe house with no running water or electricity. It was magical.

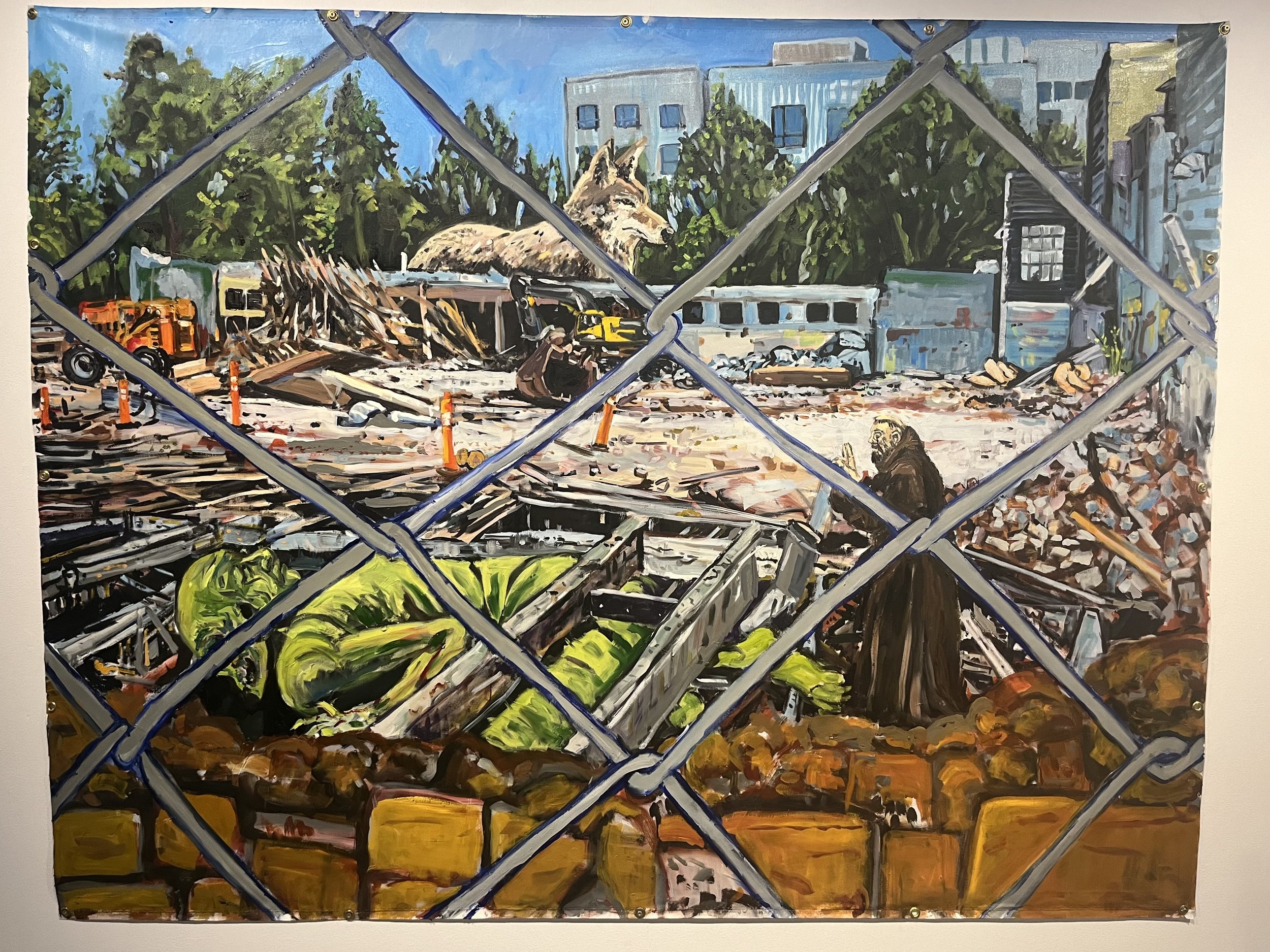

The shape of a ceramic vessel is a form of embodied knowledge. I started using majolica because I could create such vivid, painterly contrasts between the white glaze and rough red clay. I was also interested in its roots in Renaissance ceramics. This rich tradition grew out of a European desire for Chinese porcelain, but lacking the technical knowledge to make porcelain themselves, European artists developed opaque white glazes. My recent body of work is influenced by this history, particularly Delftware and the Dutch trade empire in America. The inherent violence and uncertainty that accompany a nation’s manifestation in the world breeds an enormous amount of self-doubt. My vessels explore the contradictory states, such as uncertainty and arrogance, that arise from this process.

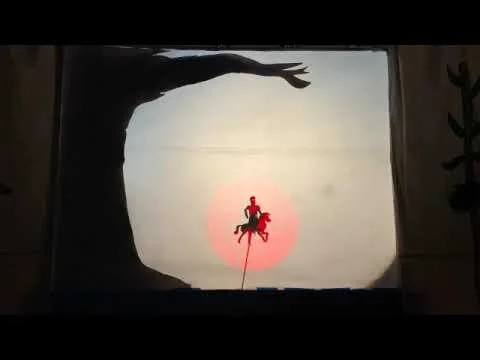

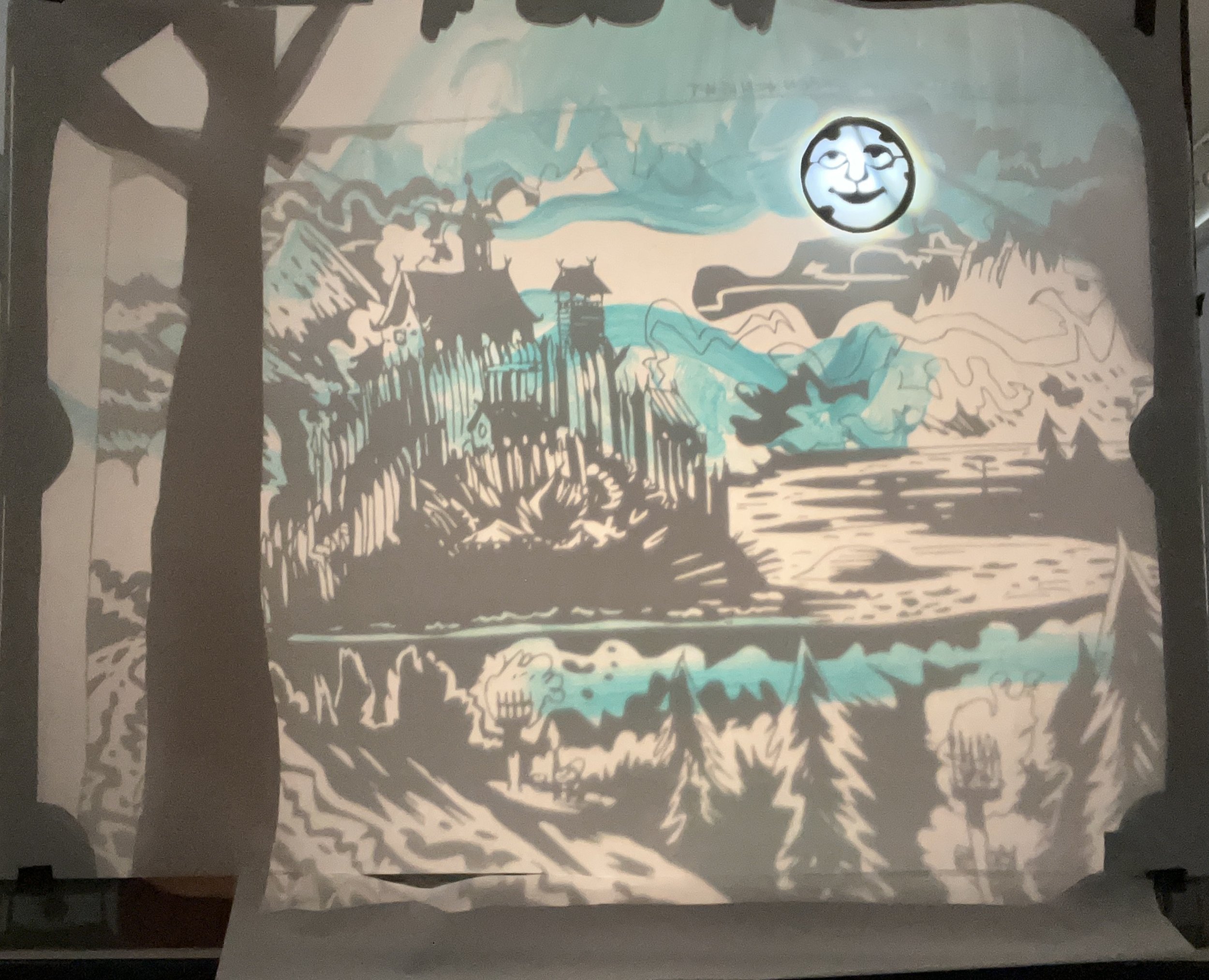

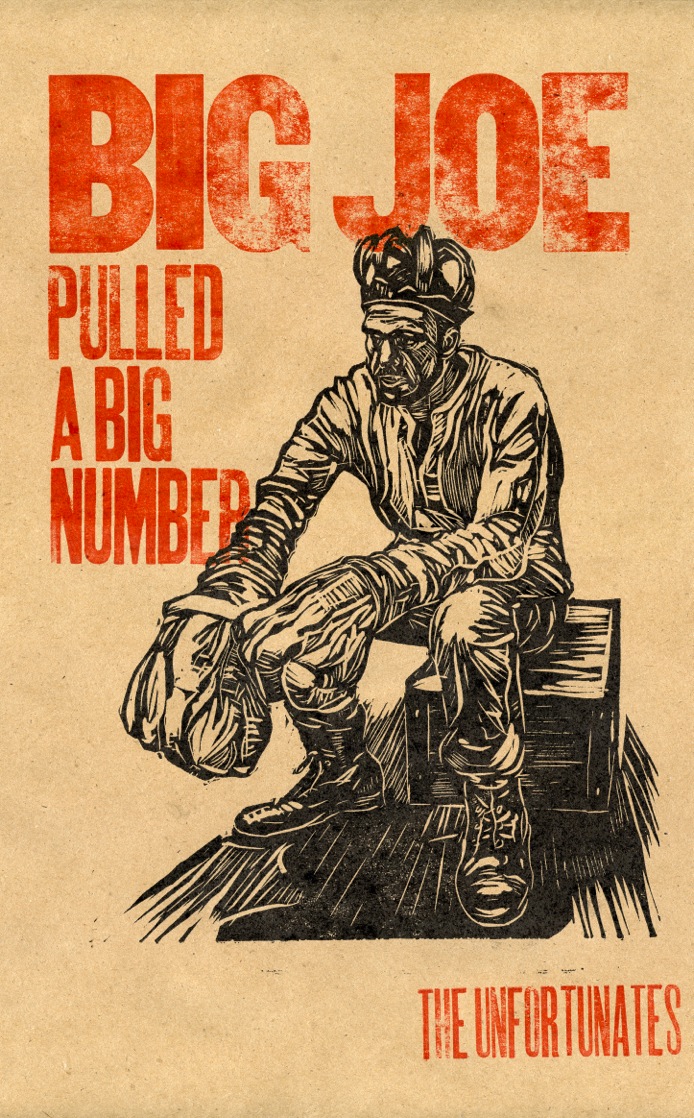

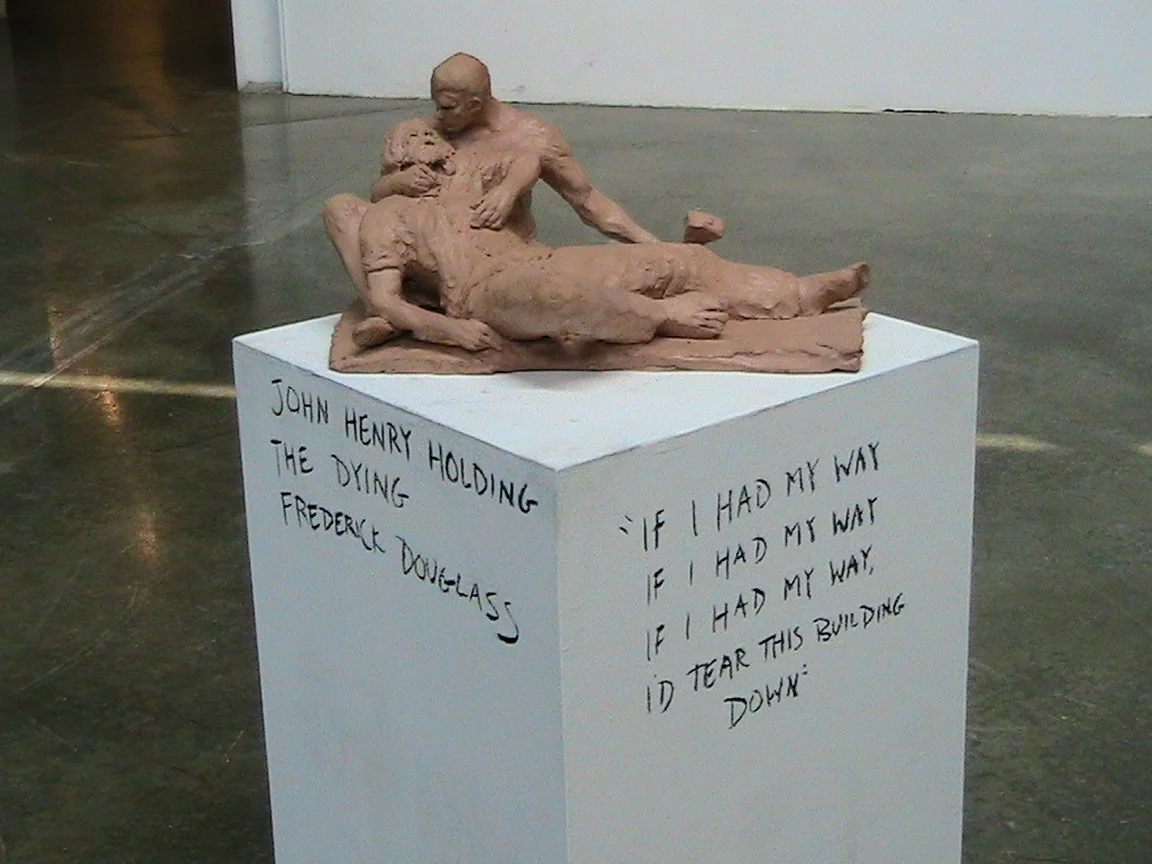

I’ve created vessels for years, but certain myths and stories have sparked my desire to breathe life into them. I read Michael Chabon’s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Klay while I was working at a residential treatment center for boys. I realized that I’d been making golems for a very long time, and that for me, they were a meditation on the relationship between strength and power. The myth of the golem became the guiding metaphor for an ongoing body of work. The many faces of masculinity are also very important to my output. What is a man? What is a hero?

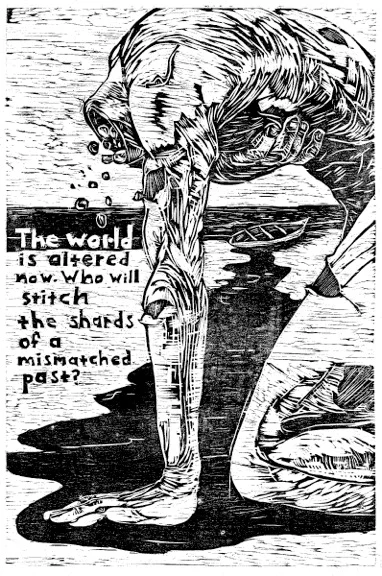

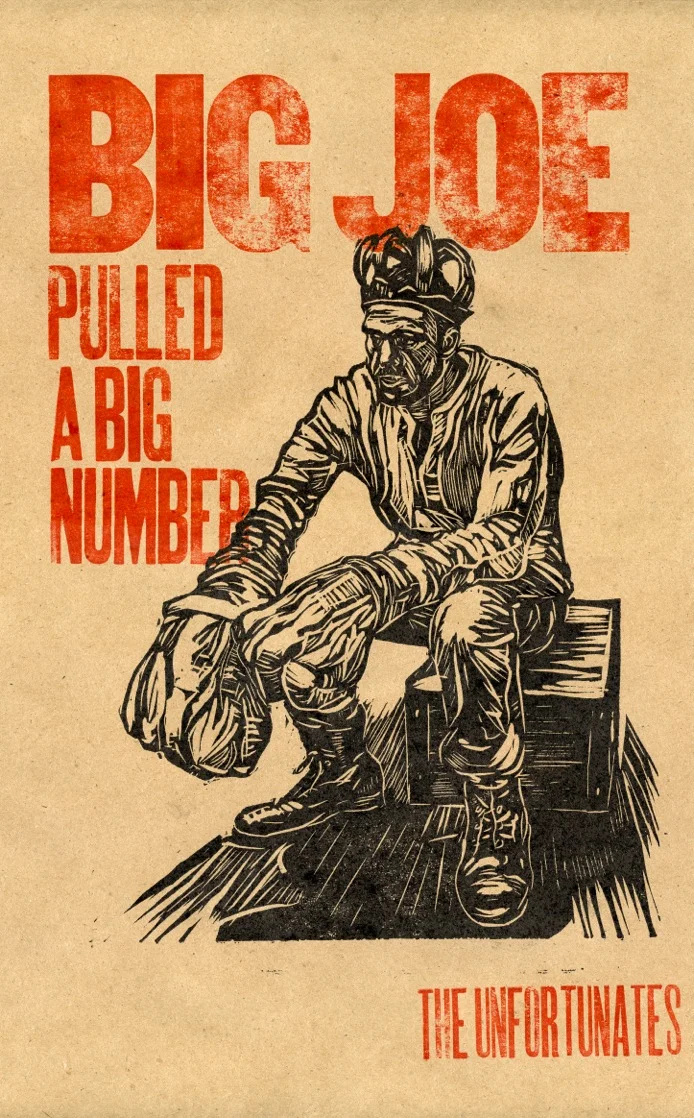

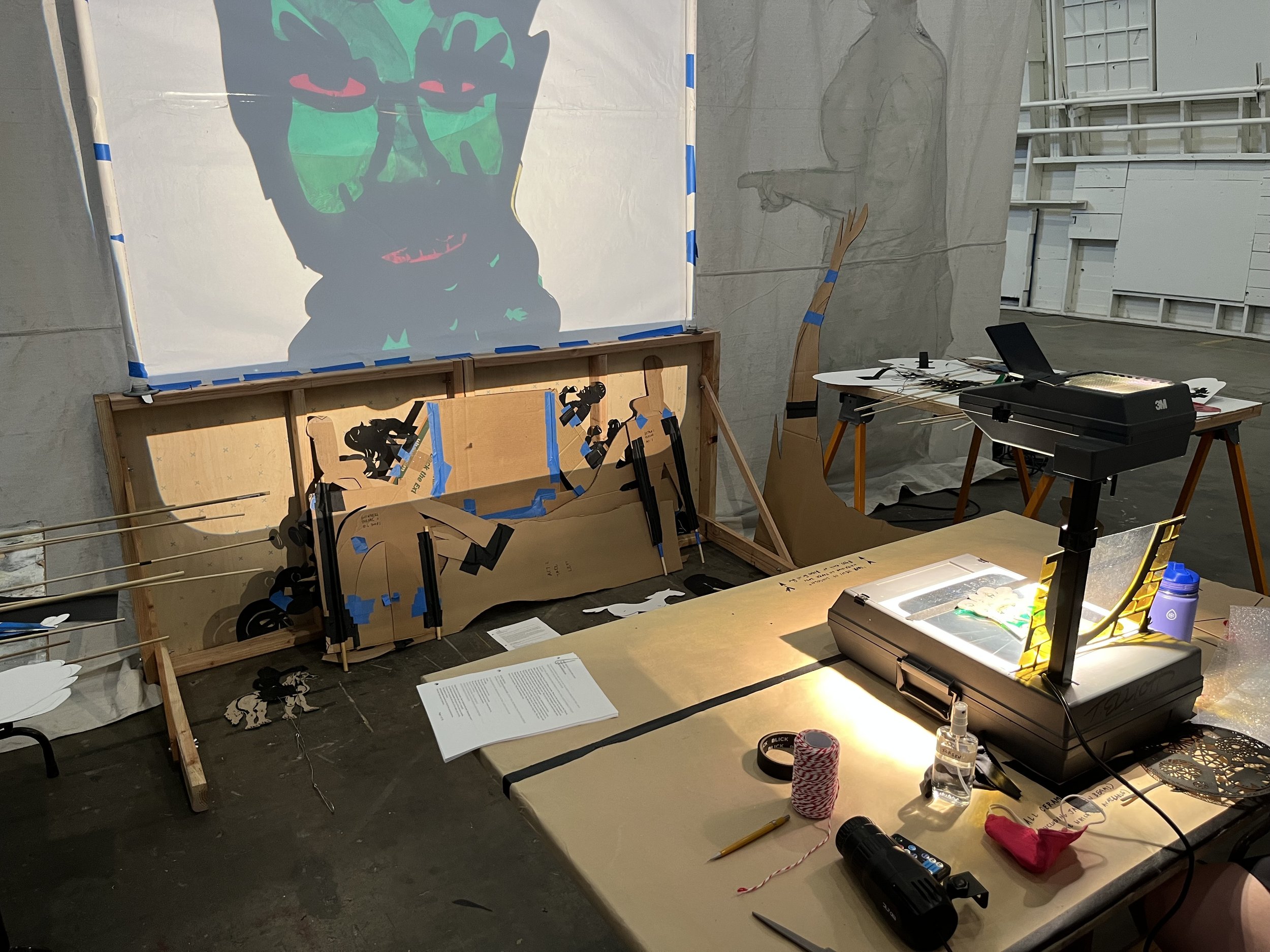

Vessels, myth, the written word, and narrative are my foundations. Because of my work with comics, I learned the value of sequential imagery. I see comic cells like ceramic shards that possess a physical dimension—they can be manipulated and assembled, spatially, to enrich a narrative and connect it to other physical objects. I think this concept has been with me from my earliest days working with ceramics, and has shaped my relationship to narrative. The vessel represents the confluence of the domestic (storage jars), the temporal (the ashes of a loved one), and the eternal (ritual and ceremony).

Some of the vessels and pots I make I also use, and that’s when they come alive. The cake platePyrrhic Victory contains an image of one of General Custer’s horses; it adorns the object with a kind of stateliness. But when someone uses the plate for sticky buns or Bundt cake—then what? I want to reside in the interstices between fine art, craft, and comics, searching for ruptures and spillovers. It enlivens the whole field to let wild cultivars breed into the monoculture.

— As told to Stephanie Snyder for Artforum, April 16, 2012